FILES BEGET FILMS: HOW INDIAN BUREAUCRACY MADE DOCUMENTARIES

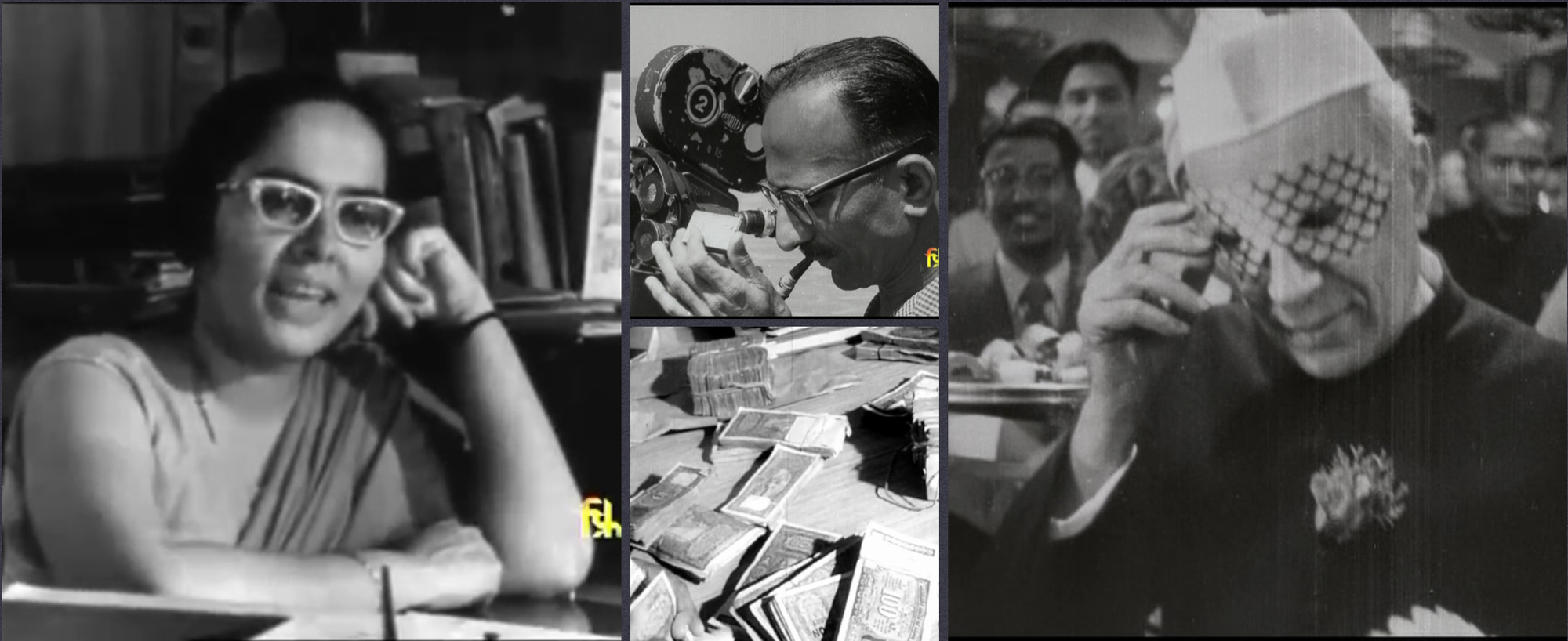

In the dark and dank offices of Films Division of India’s (FD) headquarters, there reigns a mise-en-scène of bureaucratic red-tapism all too familiar if you have visited any government office in India: faux-leather chairs draped with white towels (a common hack to keep dry in oppressive tropical humidity) next to wooden desks covered with transparent glass, although whatever pictures are on display would be obscured by piles of official documents. Outside these rooms, the halls are lined with unending stacks of metal film cans, the end products of this institution’s documentary film productions meant to show India to the people. Looking at these piles of paper and celluloid together, the words of one of the most well-known Indian documentary filmmakers, S. Sukhdev, come to mind: “Films can be born and also die in a file, it is not the fault of the file, it belongs to no one, it can always be pushed upstairs.” Sukhdev’s acid remark makes one wonder, what does it mean for the government file to give birth to a film but also drain it of life? What happens to a file when it is “pushed” into musty rooms somewhere “upstairs”? What agency, if any, do the people who “push” the files have? And, if the files don’t belong to anyone, how do they exercise so much power over which films “live,” and which “die”? Could it be that India’s bureaucratic culture is more than an impediment to creativity, but instead a primary life-giving and life-taking force for filmmaking? These questions lie at the heart of this book.

Files Beget Films tells the story of a colossal documentary filmmaking enterprise that showed India on film, through a behind-the-scenes look at the complex operations of power, patronage, experimentation, subversion, and dysfunction that governed filmmaking at FD. Tracking the relationship between documentary film-making and bureaucratic file-pushing during the 1960s and 70s—two decades that saw intense experimentation with film form as well as periods of wars and national emergencies—the book conceptualizes FD’s film practice as “sarkari,” a Hindi-Urdu word implying practices belonging to the realms of government and bureaucracy. Files Beget Films explains how documentary film practices of the government of India emerged not in spite of but precisely because of the bureaucratic mode of (dys)functioning. Drawing from years of original archival research, the book brings together the study of documentary filmmaking in conversation with the fields of postcolonial bureaucracy, archival studies, and media infrastructures in the Global South. It demonstrates that the lines between creative agency and authoritarian agendas in filmmaking at FD were often blurry, that film form and mandates were subjects of constant negotiations, and that the realm of documentary film actively comingled with the realm of popular cinema. The book’s implications extend beyond South Asia to enable new understandings of the relationships between film, state, and institutions.